Bolivia’s culinary scene has recently burst onto the global stage – and leading the charge is Marsia Taha, a Bolivian chef and researcher whose work extends far beyond the kitchen.

Marsia first came to prominence at the helm of Gustu, the pioneering La Paz restaurant that put Bolivian fine dining on the map, Now with her own project, Arami, she turns her attention to the Amazon, drawing on years of travelling through the country’s remotest corners.

Named Latin America’s Best Female Chef 2024, she is part of a new wave of chefs reshaping Bolivia’s culinary landscape – not by looking abroad, but by turning their gaze inward. We spoke to her about what Bolivian cuisine means to her, where best to experience it, and the legacy she hopes to leave.

Tell us about you – how did you get into cooking, and how did you develop the philosophy that you have today?

As a very young girl, I lived in a house full of women – including my grandmother – but none of them cooked. Not my aunts, not my mother, no one. So I didn’t grow up with that traditional culinary influence from the women in my family. But my grandmother loved to eat, and she was the one who introduced me to local markets, street food, and traditional Bolivian flavours.

When I was eight, my mother remarried the man who is now my father, Astro. He was the first person who truly influenced me gastronomically. He loved to cook, and cooked a lot at home. I would help him – I was his kitchen assistant, of sorts – and that’s where I had my first real contact with food, cooking for family and friends. I realised how much I enjoyed it, and my family noticed that I had a real talent for it – the kitchen became a place where I always felt comfortable.

Even so, I never imagined it as my career. It was my mother who suggested I go to culinary school, 18 years ago, when there was only one in Bolivia. Since then, I’ve never stopped cooking.

Bolivian’s food scene is undergoing a major renaissance, in no small part thanks to your work – but its cuisine still remains unfamiliar to many. How would you define it?

Bolivian gastronomy is incredibly diverse, reflecting the country’s vast geography and its many cultures and ecosystems. In the popular imagination, Bolivia is often seen as an Andean country, but in reality most of its territory is Amazonian and lowland. We have the Amazon, the valleys, the Chaco, and the Andes… all of which gives rise to a huge diversity of people, cultures, products, and flavours.

It’s important to understand that our cuisine has two histories. Firstly, there’s our traditional cuisine – the dishes that Bolivians celebrate, reclaim, and eat every day, a combination of native ingredients and those introduced during the colonial era. Then there’s our pre-Hispanic cuisine, a way of cooking that remains relatively untouched and is preserved in indigenous communities. These communities are the great protectors of ancestral techniques and native ingredients, passing them down from generation to generation.

Our pre-Hispanic cuisine is perhaps less well known, but it’s the one that inspires me most. We’re not inventing anything new – we’re rescuing and making visible what has always been there, but hasn’t always been given its rightful recognition. That’s a big part of our work.

Imagine we’re visiting Bolivia for the first time and want to understand the country’s food culture and biodiversity. Where should we begin?

I would allow at least ten days to explore, because Bolivia is a big country. You could start in the Andes and descend into the Amazon, or the other way around, to help your body adapt to the altitude. Personally, I’d start in the eastern part of Bolivia in Madidi National Park, north of La Paz, which is considered the most biodiverse park on Earth. You eat very well there, there’s strong community tourism, and the wildlife and birdwatching are incredible. It’s an expedition that I’ve done several times, and it changed my life.

From there, I would continue to Rurrenabaque and travel into the Pampas and the jungle on a three-day expedition, another great place to experience Amazonian ingredients and flavours.

Then I would head up into the Andes to La Paz. The city’s food culture revolves around the popular economy of the streets, and there’s an extraordinary diversity of street food and flavours. I’d make time to visit the markets, which are the soul of every city, and also to visit the restaurants there. La Paz has an incredible food scene, with many talented chefs working with local ingredients and proposing ideas rooted in Bolivian identity.

You can’t miss Uyuni, the largest salt flat on the planet – the landscapes there are truly breathtaking. And if I had a little more time, I would head to Sucre, Bolivia’s constitutional capital. There, I’d eat at the ajicerías and picanterías. Sucre has some of the country’s best ají peppers and peanuts, and a strong tradition of rich, flavourful stews.

We have a weekend in La Paz. Where are you taking us?

My first stop would be the markets – if I had to pick just one, it’d be Rodríguez Market, in the city centre. The street food there is incredibly diverse and delicious, and available at all hours.

From early in the morning, you’ll find stalls serving guatiaque, which is a native soup from Lake Titicaca that brings together all of the ingredients of the Altiplano: native fish, freeze-dried potatoes, coa – a high-altitude herb – and local Andean tubers.

As the day goes on, I’d stop for empanadas: a good salteña, filled with meat and broth; a tucumana, deep-fried and served with a whole line-up of sauces; a yaucha, baked with fresh cheese. My favourite salteña is from La Gaita, on Potosí Street. We also have fried empanadas served with api caliente, a warm, thick drink made from white or purple corn.

Later in the evening, I’d eat a good anticucho (a skewer of thinly-sliced beef heart cooked over a grill) or tripitas (crispy grilled intestines) from a market. Then a visit to one of the more traditional, family-style restaurants for a taste of everyday Bolivian cooking.

Of course, I’d also want to show the other side of La Paz, the contemporary food scene. There’s a whole new generation of chefs telling stories about Bolivia through food. I’d recommend Ancestral, Phayawi, La Rufina, and Ali Pacha, which is vegan. My restaurant, Arami, to try some Amazonian food. And, of course, Gustu.

For drinks, I’d head to my favourite bar, Bestiario, in the Sopocachi neighbourhood. It’s an artsy, bohemian space where they make incredible drinks with their own distilled spirits. There’s live music at night, and they host a lot of music festivals and gigs – it’s a hugely important cultural space.

And as for coffee – Bolivia produces some of the best. My favourite cafés are Typica Café, Hierro Bronce, and Épico. They’re super involved throughout the whole coffee-making process – they roast their own beans, work directly with local coffee producers, and treat the product with real respect.

After years at the helm of Gustu, you recently launched your own restaurant in La Paz, Aramí. What’s the story behind the name, and how does the restaurant reflect your vision for Bolivian cuisine?

Aramí means “piece of sky” in Guaraní, one of the native languages spoken in Bolivia’s Amazonian lowlands. It’s a tribute to everything we’ve learned about this vast territory: its ingredients, its techniques, and the communities that preserve and transform these products using pre-Hispanic methods passed down through generations.

The Amazonian region is incredibly rich and diverse, yet remains largely unexplored. I would say more than 80 or 90 percent of its ingredients never even reach the cities or markets — and if they are no longer consumed, there’s a great risk of losing them altogether.

Aramí celebrates the diversity of the lowlands through a cuisine that honours the ingredients and tells the story of each product — where it comes from, who produces it, and which part of the Amazon it belongs to. From our drinks to the dining experience itself, it’s about storytelling and paying tribute to the Amazonian pantry.

What can diners expect from an experience at Arami?

When people step into Aramí, they find a warm, welcoming space. The decor isn’t maximalist like the Amazon itself, but it draws heavily on Amazonian elements – wood, natural textures, earth tones and patterns – while maintaining a calm, elegant feel.

We offer a short tasting menu and a small à la carte menu with starters, mains and desserts, each with five options. Through the menu, we want to give diners the opportunity to taste a piece of the Amazon and experience its diversity and incredibly rich flavours, which are unfamiliar to most.

We use a lot of Amazonian fruits which are characterised by having very bold, concentrated flavours, and we also work extensively with Amazonian fish, which are typically very bony but packed with flavour. For example, piranha. It’s usually very complicated to eat, but we debone it entirely, while keeping the head and tail intact so diners can see the full fish – teeth and all. We look to really enhance the strong flavours of our ingredients, rather than mask them, so that each fruit, each element — mushrooms, Amazonian nuts, oils, fish, or game meats like caiman — is the protagonist of the dish.

Alongside the restaurant, you’re also the co-founder of the Sabores Silvestres project. Tell us a bit more about this initiative – what are its goals, and what have you achieved?

The Sabores Silvestres project was launched in 2018, together with Gustu and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). It has been an extraordinary learning experience, allowing me to travel extensively and discover many indigenous communities, endemic products, and pre-Hispanic techniques that are still very much alive today.

One of the main goals was to document native ingredients and record the traditional techniques used to transform them, passed down through generations. Another important objective was to create direct market opportunities with indigenous communities — to meet the fishermen, the paiche producers, the Tacana harvesters of caiman meat — people we might otherwise never have access to from within the city.

The project helped break those geographical barriers, allowing us to carry out research in situ and work hand-in-hand with communities.

Over the past year, the project has been on pause as WCS has had to focus on urgent environmental crises in the Amazon — fires, floods, climate change. But Sabores Silvestres will continue for many years to come. It’s a beautiful collaboration, involving not just chefs but scientists – biologists, botanists, agronomists – who ensure that our research is serious, sustainable, and meaningful.

What does the future hold – do you have any new developments or projects on the horizon?

Right now, I’m very focused on the restaurant. In the short term, my partner Andrea Boscozo and I are working on opening a wine bar on the second floor of the house where Aramí is located. The idea is to showcase criolla grape varieties, not just from Bolivia, but from across the region.

Aramí is a concept that is 100% Bolivian, but with the wine bar, we want to broaden the focus and highlight criolla grapes from all over Latin America. It’s a project we’re building little by little, and that’s our next immediate goal.

In the longer term, I want to continue researching and travelling within Bolivia. Even though I’ve explored a lot of the country, there’s still so much left to discover. I also want to keep representing Bolivian cuisine abroad, sharing our flavours and products with the world, and encouraging the world to turn its gaze towards Bolivia.

What do you hope your legacy will be?

I hope to set an example for young people now and in the future: to leave them with a cuisine rooted in their own identity, to encourage them to look inward, to feel proud of what they have in their country. I want to show that it’s possible to have a successful career cooking Bolivian cuisine and using Bolivian products.

I believe Latin America is experiencing a new awakening, like a giant that has woken up and is starting to recognise and take pride in its own products and identity. When I started, that didn’t exist. At 18, I wanted to leave the continent to study in Europe and learn foreign techniques, Spanish and French, which I admired and still admire. I’m not criticising that, as I learned a great deal. But I believe Latin Americans need to look inward first, learn from ourselves, and then look outward. That is the small legacy I hope to leave. Many chefs are already doing it, and many did it long before me, but it remains essential.

I also want to show Bolivian women that it is possible that we can lead, start businesses, and have an important place in the industry. Seeing women doing interesting, successful things inspires others to say, “If she can, I can too.”

Related Stories

A Food & Wine-Lover’s Guide to Peru with Laura Graner, Sommelier & Food Journalist

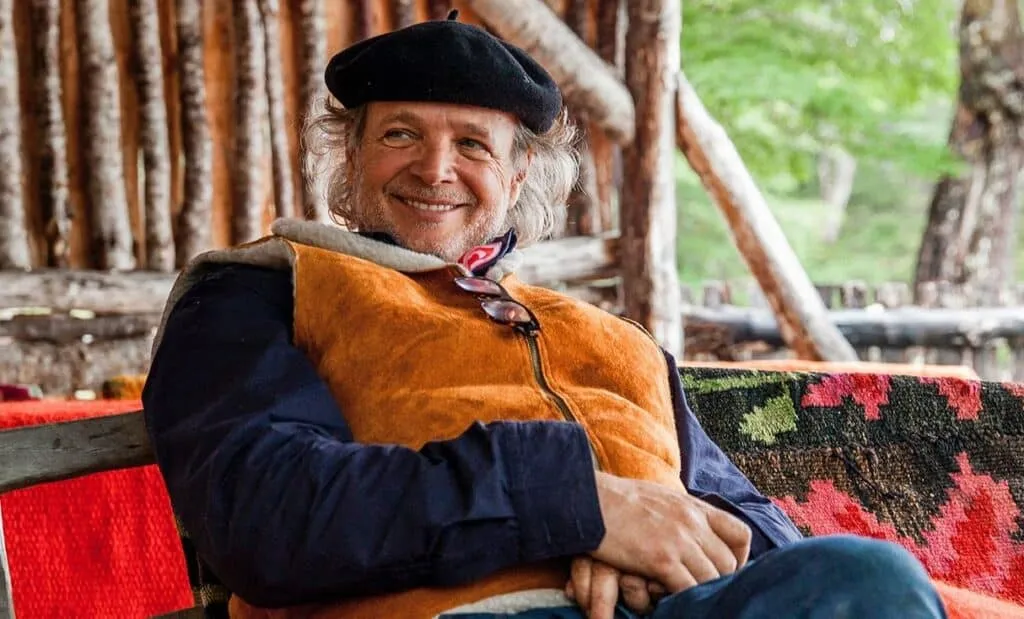

An Interview with Francis Mallmann, Argentina’s Legendary Open-Fire Chef

Where to Eat & Drink in Buenos Aires: A Guide by Sorrel Moseley-Williams