New York–based photographer Michael Turek has spent two decades refining the art of looking.

His work, published in The Financial Times, The Guardian, The New York Times and the Paris Review, bridges documentary and fine art. A committed advocate for film, he approaches photography as a form of enquiry: a way of slowing down and paying closer attention.

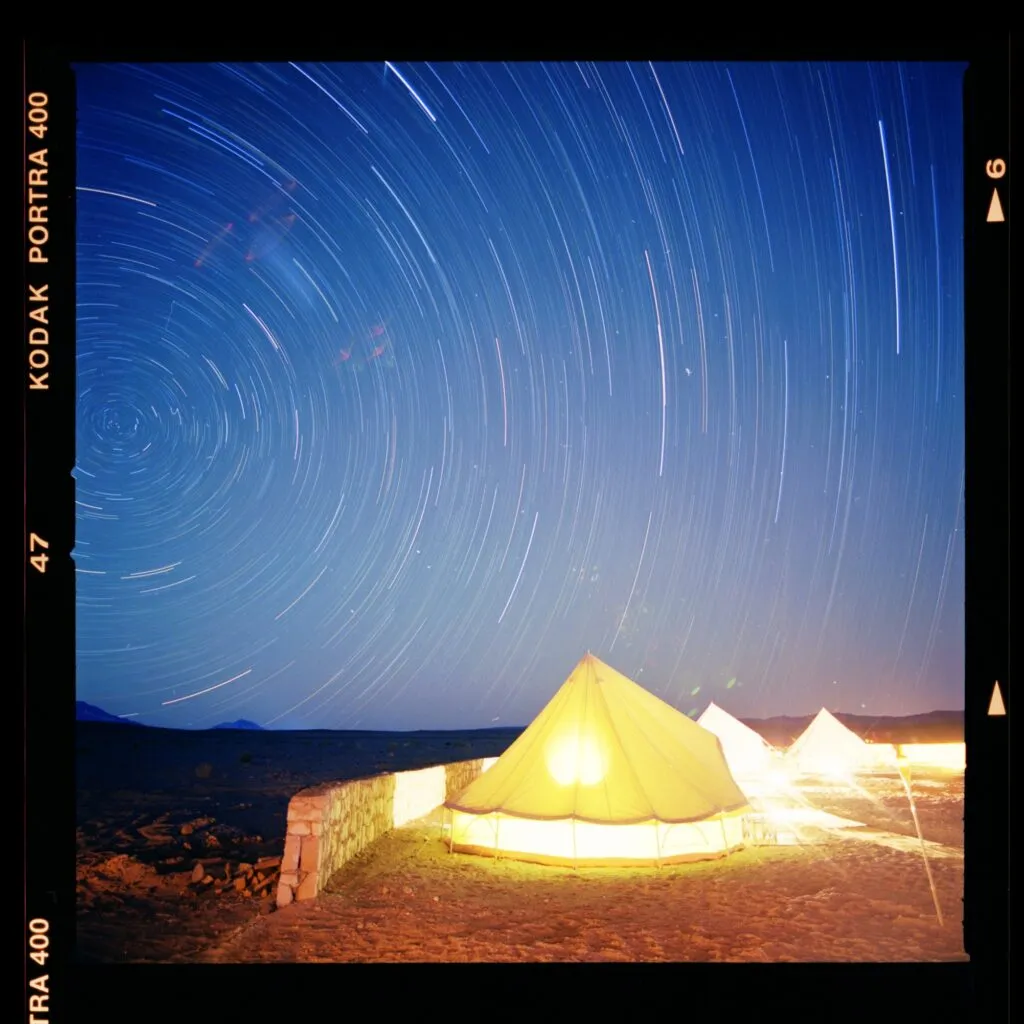

This November, he joins PSA’s Harry Hastings in leading a photography expedition over the Andes, travelling by 4×4 from northwest Argentina into Chile’s Atacama Desert, in collaboration with the Kodak Camera Club.

Ahead of the journey, Turek reflects on the merits of travelling with a camera, why he prefers film over digital, and how to look – and shoot – with greater intention.

What drew you to travel photography – and what keeps you fascinated by it?

Taking a camera enhances the whole experience of travel because you’re engaged in trying to aestheticize what you’re seeing. You’re putting the world in a rectangle, and it brings you into a heightened level of awareness and intentionality.

Susan Sontag is often credited with saying that photography is the act of pointing. When you see something that excites or inspires you, the instinct is to point – Hey, look at that, that’s cool. The camera formalises that instinct. In the time it takes to see a scene and put the viewfinder to your eye, you ask yourself: what about this scene interests me?

You choose what to include, what to exclude – and those decisions become your voice, your paintbrush, your identity.

You’re a fierce advocate for film. Why?

I find analog photography to be more creatively productive because of its restrictions. You know it’s not unlimited, so you approach each scene with greater consideration. You might take a few extra seconds to meter the light or to double check your framing before pressing the shutter, but that extra moment makes your photograph so much more intentional.

Film also helps me to create new compostions in a linear fashion, rather than getting hung up on any one frame. With digital, you lift the camera, take a shot, check it, and then likely take another one too similar to the first – you end up walking in creative circles, over-perfecting the same shot. And it’s difficult to resist looking at the LCD screen – you’d need to be a strict Zen monk. With film, you can’t do that – it forces you to make true variations.

When I shot digital, I’d invariably send editors seventy-five versions of the same picture, to their great annoyance. Once I switched to film, my submissions had real variations, and they said, “Wow, it’s so much easier to edit your work!” The limitation of film made my work more efficient.

On workshops, it also changes how you end your day. If everyone’s shooting digital, you spend the evening sitting in front of open laptops, people comparing each others images, which can feel a little competitive. With film, you can’t do that. Instead, you sit with a glass of wine and talk with one another about what you saw that day that inspired you, what you think you did well, where you think you struggled – you talk about aesthetics. It becomes a meaningful conversation about the process that really helps for the next day.

What, to you, makes a ‘good’ photograph?

I like it best when photographs are beautiful and bizarre at the same time. I’m drawn to things that are objectively beautiful, of course, but they’re a dime a dozen. But if you can have both – something aesthetically pleasing in harmony with something askew or slightly jarring that makes you look twice – that’s a good photo.

Ultimately, the purpose of taking photos is storytelling – it’s a type of language. And like good writing, there’s text and subtext, analogy and metaphor; it’s more than just straight reporting. That’s where the pleasure lies.

Tell us about the gear you’re packing for your upcoming expedition to Argentina – and why each camera earns its place in your bag.

My main camera will be a medium format Pentax 67 — it’s big and heavy, but great for the landscapes.

I’ll also bring a fifty-year-old Horseman Convertible. It has a few advantages; it’s much smaller and lighter than the Pentax, and it doesn’t need a battery, so you can keep the shutter open for six or seven hours without draining power — essential when you’re shooting through the night. Another fun fact is that it has interchangeable film backs, which means halfway through a roll you can switch to a different type of film.

And I’ll take a smaller 35mm camera, which I use it for some ongoing projects, such as Sleeping on the Job. I set it up at the foot of the bed and let it expose through the night while I’m asleep. The light from a socket, a phone, or an alarm clock slowly colors the scene. The results are strange and beautiful – a great souvenir of all these places I’ve slept in but can’t remember.

For someone who’s just starting out, what one camera would you recommend?

A brilliant camera that I always suggest for people starting out with film is the Pentax K1000. It’s a joy to use, and it looks really cool. It’s an old 35 millimeter SLR type camera that’s no longer in production, but was one of the most manufactured cameras in history. It’s a lovely little tank of a camera – it just has three things for you to control: aperture, shutter speed and focus. But as the saying goes, the more professional the camera, the less it does for you.

Every photographer knows the frustration of finding themselves somewhere extraordinary at the wrong time of day. What are your tips for dealing with bad light on the road?

This was one of my biggest frustrations when I was in Argentina last time: passing through these amazing landscapes and thinking, can we stay for an hour? Can we stay until tonight? But we had to keep moving. Unfortunately, I know we’re going to come across that scenario again on our upcoming trip, as we’re travelling such long distances. And when you take a picture on your phone, it looks pretty awful because the sun’s straight overhead and too contrasty.

Film can be a solution. I’ll be shooting on Kodak Ektar 400, which has amazing exposure latitude, so I can over expose drastically – five, six, seven stops – and the colours will begin to shift in a curious way, more pastel, more painterly. The grain begins to reacts and expand with all the extra light and the image takes on a pointillist quality, like a Seurat painting. It’s an effect you simply can’t achieve digitally, and a great strategy for photographing a landscape in harsh light.

How do you approach photographing people you’ve just met — what do you do before lifting the camera?

I’ve noticed that many of my best portraits are taken when I’m seated – I’m more relaxed, and more observational. Sitting also makes you less threatening, and from three and a half feet off the floor, the vantage point can feel more intimate.

A tripod helps, too. Cameras are so intimidating, like a mask that hides your face. By putting the camera on a tripod, I can still look at the person when I press the button. The act of portrait-taking becomes more formal – they take a deep breath, put their shoulders back, and react to the respect you’ve given them by making it an event. Also, if they suddenly loosen up after that first image, the camera will be in place and ready to capture that as well.

The ‘foreign gaze’ has become a big talking point in photography. How do you navigate that as a traveller behind the lens?

I’m not interested in spy shots. You see it all the time – long-lens photos of someone’s face from across the street or across a market. Sometimes those images can feel a trophy and without real intimacy.

Instead, get close. Ask, what are you doing? Where are you going? Have a conversation. Let them “smell” you, metaphorically speaking. I’m not saying that portraits must have eye contact, but I prefer an image that implies a relationship between you and the person being photographed, where their body language shows that they know you’re there. It’s much more intimate when there’s a mutual acknowledgement of presence – less like a human zoo photo.

Compositionally, I avoid tight headshots – I don’t want to make yearbook photos. Focusing solely on someone’s features can exoticise and feel exploitative. I prefer to see wider context, and find that can be more dignifying.

How do you go about planning and researching a photography expedition – what makes it a success?

Guides can make or break a trip – they have the keys to the kingdom. For instance, Santi, who is leading our Argentina expedition, is a pro; we’ll be relying on his expertise, engaging his local knowledge of what places could be interesting at what time of day. It allows for real spontaneity and adventure.

Before I go on a trip, I also spend a lot of time looking at photographs online. It’s helpful to know how a place has been visualised in popular culture – once you’ve seen all the postcards, you know what images to avoid.

For anyone looking to improve their travel photography – whether film or digital – what practical advice would you give?

Start by stripping your equipment down: practice working with just one camera, and one or two fixed focal length lenses. It pushes you to make work that’s more definably yours. Think about great writers, painters, choreographers: they usually have a clear aesthetic that’s immediately recognisable. If you’re shooting with different lenses, focal lengths and mediums, it dilutes that unity of voice.

Zoom with your feet, not your lens – if your photos aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough. Those are well-known phrases, but I think they’re true. The camera is like a cyclops – it can’t see in 3D, so if you’re too far away then everything becomes flat. At times, you’ll wish you had another lens option, but find a creative way around it; often using the “wrong tool” for the job can spark something new and original.

Bring a tripod, and use it even when you think you don’t need it. People assume it’s only for low light, but it’s the single best piece of kit to improve your work. It slows you down, takes the camera off your body, and can help shift your perspective.

Finally, print your work. Don’t let those image files just sit on a hard drive somewhere. Photography doesn’t end with taking the picture; you have to make the physical artefact on paper.

—

Through his ongoing partnership with Plan South America, Michael Turek is available for private and small-group photography expeditions across Latin America.