Natural sound can alter our mood, our stress levels and even the way our brains function – if we stop long enough to notice it.

Costaphonics, founded by soundscape ecologist and musician Santiago Roberts, is built around this idea. Working across Costa Rica, the project explores how tuning into the natural world can support both wellbeing and environmental regeneration.

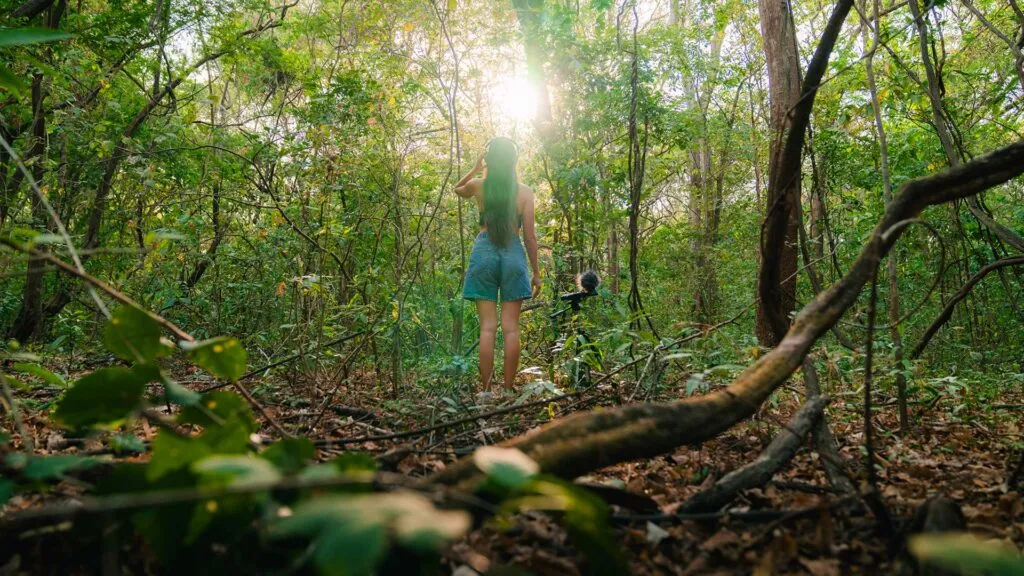

Equipped with specialist microphones and a series of structured listening exercises, participants are guided through the acoustic architecture of an ecosystem: from birds and insects to water, wind and the near-imperceptible vibrations of the forest floor.

We spoke with Santiago about the science behind the experience, what he hopes people take away from it, and why Costa Rica offers one of the richest listening environments anywhere in the world.

Take us through how a Costaphonics listening experience works.

We start with a short introduction to soundscape ecology – how it works, why it matters, and how different species use sound for different things. For example, a bat can see with sound, and a dolphin feels its environment through sonar.

We advocate for silent walking – not talking, obviously, but also quietening your steps. People walk so loudly in nature without realising; think of nature as a shrine. Being very mindful of your step puts you in the psyche of an ancient hunter and makes you far more aware of your environment.

Then we move into listening exercises. We start with a series developed by American composer Pauline Oliveros to awaken the body more fully to sound – turning off semantics and connecting with sound as it is, without trying to categorise it. We place a 360 microphone in the middle of the group and explain the theory. People try the exercise first without headphones, then with headphones, so they can feel the contrast. It’s interesting to see how the brain processes it.

Gradually, we introduce ear-cleansing exercises to dissect your soundscape. Count how many sounds you hear, and consider which ones are made by the earth, by animals, by humans. Try to stick with one sound for as long as you can, excluding all others – it’s easier said than done.

Finally, we do what we call medicinal biophony, using devices that vibrate with sound. We have hydrophones to listen underwater, geophones to listen to the soil, and devices which convert bioemissions from plants into notes. Depending on the length and intensity of each pulsation, the algorithm generates different notes. This final session is like a massage: just relax and vibrate with the sounds. It’s a very immersive experience.

Tell us a little about the science behind it – how does it contribute to wellbeing?

Our experiences are about changing your relationship with sound, and understanding how much more there is than we give it credit for. Sound isn’t something we experience only through our ears – there’s a tactile aspect. Everyone knows how it feels to stand in front of a speaker and feel sound moving through the body.

Sound has been used for healing for centuries – with bowls and instruments – but it’s only very recently that we’ve started framing it scientifically. Japanese scientists started studying the health benefits of time in nature back in the 1980s, when forest bathing was introduced to combat a rise in stress-related illnesses, but with sound, it remained largely descriptive.

More recently, scientists started analysing changes in blood hypertension levels and other physiological markers linked to sound in nature. They’ve found that it reduces hypertension and cortisol levels, helps you fall asleep faster and more efficiently, and improves cognitive abilities. Some hospitals are using controlled sound environments to replicate the sounds of certain forests at certain times, and they’re reducing the use of analgesics.

When we saw that research, it backed up what we were doing. What began as a hunch turned out to have a scientific basis – that natural sounds are doing something genuinely good for people.

What does Costa Rica offer, acoustically, that few other places can?

We can still listen to ancient rainforests here. As a country, Costa Rica holds around five to six percent of worldwide biodiversity – 3.5% just in the Osa Peninsula. It’s also the only country in Mesoamerica that has a dry forest – there’s a huge biological passage that goes from the driest area of the country all the way to the most humid area.

The dawn chorus here is incredible. That’s when the life in the forest is waking up, and you hear this explosion of crazy calls. The other chorus I love is at dusk, from about 4.30pm to 6pm, which is very different. It’s the transition from day sounds to night sounds – it’s fascinating to hear how it changes.

What first sparked your interest in the power of natural sounds?

My father works in ecotourism, and he also spent some time in the music industry, so I always had those two worlds around me. I’m the youngest of six, and all my siblings were listening to different types of music, which created a very specific interest in sounds.

I wasn’t so interested in identifying species, but more in recognising patterns, which I would use to write for my own bands. For example, I would memorise a pattern in birdsong, and then suggest it as a riff idea in the rehearsal room.

I went to music school in LA, and when I graduated, some friends of mine sent me natural sounds they were recording in Costa Rica. It was the first time I listened to those sounds out of context, and I hadn’t realised how much I missed them – and how much I needed them. I started thinking: you’ve learnt how to transcribe sound, how can you use this? Where’s the connection?

I’d also studied some psychology and always loved neurophysiology, so I was very interested in the effect sound has on the brain. I figured there had to be a correlation between how happy Costa Ricans are and the amount of natural sound they’re exposed to.

Soundscape ecology plays a big role in your work. Tell us more about that?

One of my close mentors is Bernie Kraus. He’s a godfather of soundscape ecology, which analyses how healthy ecosystems are through the sounds they produce.

He categorises sounds into geophony, which is sounds made by the earth – tectonic plates, water, wind, and biophony, the sounds of living organisms that find their frequency within that spectrum. Human beings started imitating those sounds, which became anthrophony. And then technophony came about. Originally that might have been two stones making fire – now, it could be a jet. As a musician, I realised, these are the origins of music. This is where my interest in music, nature and sound converge.

I went looking for Bernie at a festival in England and asked if I could study with him and bring that knowledge back to Costa Rica. I spent a decade studying with him while touring as a musician – visiting his home in California for several weeks at a time, reading books and asking questions. I fell in love with the field, and he saw that.

At first, it was all pretty nerdy and academic. Later, I started thinking about soundscape ecology from a commercial point of view, and it changed everything. The mission became to create something that ensures its perpetuity: to hire bio acousticians and soundscape ecologists, to make people value natural sound as a resource, and to encourage them to see it as a means to wellbeing.

Costaphonics goes beyond just tourism experiences – it’s also a record label and research project. Tell us a bit more about that?

When someone hires us, it always starts with the science. The first thing we do is record the property. We work with bioacousticians and soundscape ecologists to capture the soundscape and generate reports of what species are present, and how they interact with the ecosystem.

From there, we create digital products. We want to make it easy for people to contribute just by listening. If you go to bed and listen to these sounds while you’re sleeping, you’re generating royalties. It’s different from playing nature sounds on YouTube – usually the revenue goes to whoever made the recording, but our recordings are registered so that 50% of royalties go back to the property.

The vision is that landowners can regenerate their land and in doing so earn income through natural sounds. We’re working with coffee farms, recording their soils and creating digital products so that people that buy the coffee can scan a QR code, listen to the farm, learn what’s there, and generate royalties for the property.

There are others doing soundscape ecology and recording sounds of nature, but we’re the only ones that have the experiential side. I call this trifecta ‘audioregenerative ecotourism’. Regenerative because of what it does for a person – but also for the environment, its sounds, and the future of ecotourism.

What next for Costaphonics?

At the moment, we’re training a team – four people who’ve spent the past few months learning soundscape ecology, recording techniques and how to guide the experiences. Eventually it won’t be Santiago-centric – the idea is that this grows beyond me.

We’ll soon be officially featured alongside platforms like Listening Planet, contributing our own recordings and bringing in artists to create new work in natural environments.

I do have a big fear of over-commoditising nature. I like the recordings and the fact that people can listen to them, and that there’s a pool of about 300 million people in the world actively listening to sounds of nature. But how many of those people are actually thinking about what they’re listening to? If it becomes too commodified, people might stop going to those places altogether. That would be like never going to a music performance – you have to experience it in person.

—

Santiago will lead a Costaphonics listening session at Montezuma Sanctuary, our upcoming retreat at a private hacienda in northern Costa Rica, from 16-21 July 2026. He is also available to design private listening experiences across Costa Rica.