Tom Hollander in Colombia… with Plan South America

As originally published by The Times by Tom Hollander. After the success of The Night Manager, Tom Hollander wanted a new adventure. He found it in South America’s most magical country…

Colombia is emerging like a phoenix from more than 50 years of war. And it’s beautiful. So please don’t come here. You’ll just spoil it.

Don’t get me (Tom Hollander) wrong, they’ll be pleased to see you. But I’m scared you’ll ruin it, and I’ll have to spend the rest of my life complaining that Colombia isn’t what it used to be. Like people who went to Ibiza in the 1960s. Like people who did almost anything in the 1960s.

But my job isn’t to put you off. My job, regrettably, is faithfully to describe my experience of Colombia in a widely read national newspaper and thus become part of the process that destroys it.

So, yes, if you want to see the real Colombia, buy a ticket to Bogota tomorrow. Because it’s amazing, and it’s at such a propitious, providential, optimistic moment in its history that there’s a good chance you’ll witness something inspiring. The people are so charming, so open, so keen to welcome you, that you may have one of the best times of your life. I have. And I don’t even approve of travel. Especially in countries full of poverty. Want to feel rich? Want people to stare and smile at you for no apparent reason? Want to feel humbled and moved by squalor and human misery on a scale even worse than that imposed by the EU? Then go on holiday to a developing country. Preferably one where they haven’t met too many Westerners, think your pasty skin and sensible hiking gear are exotic, and find you personally attractive because you might be a ticket to a better life. Go. It does wonders for the spirit.

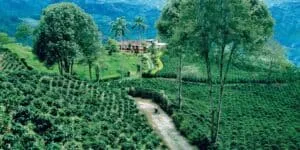

Colombia offers that, but this is not a country for cynicism. I have been here for a day shy of two weeks and, in the best way, it feels far longer. I have walked in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, cycled through coffee and cacao plantations outside the city of Armenia, and danced salsa in the Caribbean glory of Cartagena and on the streets of the crazy, smoky Andean capital, Bogota. I have sweated and roared with crowds of strangers as Colombia went to penalties against Peru (and I don’t even like football).

I have seen plant life of unimaginable variety in landscapes of miraculous fecundity. I have eaten two varieties of ants, some caiman and mangos straight from the trees. Of the ants, the first – the fat-arsed one, in a restaurant in Bogota – tasted like a mixture of smoky, crackly popcorn and something else that I can only describe as “ant”. The other, the tiny one – a tutti-frutti – was eaten in multiples, fresh off a log in the jungle. They explode in your mouth with a futile, citrussy, tingling death throe.

The caiman, defeated somewhere else and served quite safely with a side of Amazonian tubers, tasted a bit of muscly mud, slightly of game, but mostly of a dinosaur.

I have travelled alone, but have never been alone. I have met people who only ever drink water from rivers because they live by them and they are crystal clear and flow down from glaciers. I have been greeted by people who are not jaundiced or suspicious, and who can’t quite believe we want to come to their country after so many years of strife.

Near Minca, in the north, I hiked through jungles only recently accessible since conflict stopped. With my guide, I walked 10 miles through the forest to a remote waterfall. On the way, we passed through a recently abandoned Indian village. We stood staring down at the Caribbean coast, mud and straw huts in the foreground, and far below us the tower blocks of Santa Marta, the first Spanish settlement in Colombia.

With another guide, I floated down the Rio Palomino on an old inner tube for three hours, uninterrupted jungle on either side. At one point, we passed his children and their grandmother playing on the banks. With no English, he taught me the names of some of the astonishing trees. He pointed. I repeated. A little chant. Caracoli. Yarumo. Ceiba. Macondo.

He showed me toucans as they flew, roller coasting down and up, down and up, because of their too-heavy beaks. He reached into the water and threw sand into a tree above our heads until a 3-foot-long blue and white snake revealed itself and slid away. We watched indigenous Kogi people walking silently along the banks behind the trees, or playing, or washing their white clothes on stones. All life by, and on, and with, a river.

Finally, as we emerged calmly at the Caribbean, a storm broke and the light turned pink neon. We got on his fat friend’s motorbike and the three of us bounced up through their village, back into the jungle, back to the collection of huts round a lodge where I was staying. Attached to the handlebars by a hook in its mouth was a huge, stripy fish. A jurel, for the fat man’s family. Without stepping off the bike, we dropped it off with his wife, who put an arm out to take it, giving her husband a look of vague amusement. Was it the fish? Probably it was the sight of three men and two giant inner tubes on a small motorcycle.

Colombia is a country of unimaginable riches in its natural heritage, and its soil. Its fertility fosters astounding plant life – the cultivated landscapes of Europe seem sterile and exhausted in comparison. Experiencing a dawn chorus in Colombia is like hearing the Berlin Philharmonic after a music-hall act featuring a washboard and a kazoo. Though there has been much deforestation, 20% of the world’s bird species live in a country that is still 52% forest. Nearly every type of climate on the planet seems to exist in this one country and most sorts of humans in its population of 48m. Diversity here is the rule, not the exception.

In the Colombian version of boules – a game called tejo – players take it in turns to throw metal pucks at lumps of gunpowder until they explode. It’s a good metaphor for a country that is recognisably European yet wildly adrenalised at the same time. And clearly Colombia’s reputation for violence has made people think twice about visiting it. But those days appear to be over. At no point did I feel unsafe. Not once. On the contrary, I experienced only warmth and kindness.

My last day was June 23. Brexit day in the UK – in Colombia, the day the Farc guerrillas and the government agreed to put down arms in a ceasefire ending 52 years of conflict. So. You should go there if you can.

As a relatively untravelled country, even by its own population, Colombia is not entirely geared up for tourists, and it’s not always simple to get around. One solution is to let someone who knows what they are doing organise all that for you. My tour operator was Plan South America. They’ll advise you of the most interesting places to eat, sleep, and dance, and set you up with guides along the way: a historian in Cartagena, a botanist in the jungle, a biologist who explained the production processes at coffee and cacao plantations, and, in Bogota, both an art expert and a food writer. If anything needs rearranging while you’re there, they’re onto it by return of an email. They’re not cheap, but they are good.

Oh, one thing you should know. If you want some cocaine, please don’t go to Colombia for it. Seriously. It’s like going into someone’s house and asking to take a shit on their carpet. Don’t insult them.

Colombia is only a few years out of a nightmare in which those cool, exciting narcos you can watch on Netflix terrorised the population.

On a sliding scale, that goes from having to move house, to having body parts cut off, to watching your loved ones get gunned down in front of you. Since 1958, approximately 220,000 people have died and more than 5m people have been internally displaced by conflict that has been funded, fuelled by or fought over cocaine. So don’t come here for that. It’s not cool.

I met a man called Gabriel, a bright-eyed lawyer working to rehabilitate victims of conflict here. He described to me the idea of “the Macondian way of living”, after the fictional town invented by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, where somehow illogicalities and absurdities are accepted as a cultural norm.

In One Hundred Years of Solitude, the character of Mauricio Babilonia is constantly swarmed by yellow butterflies. Among many wonders here, I have seen multiple miraculous flights of butterflies. On one occasion, they even danced around my car, like intelligent confetti. In books, the intertwining of the ordinary and extraordinary is called magical realism. In Colombia, it’s merely a description of your surroundings. Not, in fact, magical. Just real.

Related Stories

Eat Like A Local In Cali, Colombia

Emerald Hunting in Colombia

Harry Hastings on Colombia

Allie Lazar | Foodie Travel Guide – Pick Up The Fork | Plan South America

@plansouthamerica