Were they dolphins or vast tambaqui? Otters or Manatees? In a sticky Amazon dawn I stood on the bow rubbing my eyes.

We were on the Rio Negro somewhere upriver of Manaus, on a boat slung with two decks of sardine-packed hammocks. On one side the bank was close, heaped with palms, iridescent blue butterflies, and towering angelim-vermelho covered with lianas. On the other side the river stretched out into a silvery sheet, marked with a few shivering rapids and a sleek back. As they came closer I saw that there were two dolphins, pinkish and smooth, and one of them had a smaller shadow next to it.

During the journey a Baré family had adopted me, and their little girl had dragged me out of my sweet-swelling palm hammock to look at an enormous moth, the size of my hand, which had landed on the deck in the night. It was the latest and most spectacular in a long line of visitors – a hawkmoth, a moth with grey chevron’d lines, a huge, brazil-nut pollinating black bee – and it had black-grey hieroglyphs like an ox-head in its beautiful forest chestnut, and delicate swallowtails.

When I looked up the dolphins were nearer. They, or some others, appeared at various times across the five days and nights that we were on the boat, all the way up to Sāo Gabriel da Cachoeira. Once, looking at them, I found my attention caught instead by the shore, where a large snake slid like a fat green shade along an overhanging branch of a flowering Clitoria and down into the water; another time, as I stood by the stern at night and looked for the gleaming eyes of a black caiman, I heard a hiss, and realised that the wave I was staring at was flesh, a dolphin, coasting along with us at night.

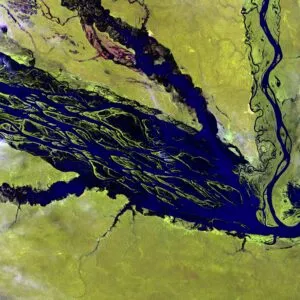

The Rio Negro has a black oily slick on its water; a peat-rich gold that asks for a Scottish salmon to lurk over the white sand in its depths. Like a peat river it is acidic and full of humic acid, the result of water running off the granite of the Guiana highlands in Columbia and Venezuela, 1.7 billion years old, and being filtered through massed layers of rainforest, a million interwoven roots filtering it for any useful remnant. By contrast the other great tributary of the Amazon, the Rio Solimōes, is cappuccino-milky, carrying white sediment from the young Andes in Peru. They meet at Manaus, in a dolphin-torn expanse where the two waters push up against each other and tumultuously mix and divide like an alchemist’s dream.

A man called Solomon took me in his canoe to run my hand through the water’s difference, where the espresso warmth of the Rio Negro is pulled in little puffs into the ice-milk of the Rio Solimōes. Then we followed his favourite dolphin “the old grey one” up to the balsa-wood villages of wooden bungalows that floated on vast lightweight logs, where they sold fresh cashew-fruit juice from the floating corner shop.

On the way back to Manaus harbour a container ship, incongruous 1,000 miles from the sea, came roaring up the Amazon behind us. Manaus’ position as the last deep-water port on the Amazon made it rubber-boom rich, and as the tide withdrew it was left with belle-époque buildings of exquisite charm which are now being restored in a new boom.

Among them the opera house reigns supreme; gilded boxes and stalls, with seven hundred and one jacaranda and red-velvet seats impatient for an audience. On the stage curtain the Tupi goddess Uiara lounges in the cataracts of the meeting waters, surrounded by swags and roses. The legend is that she was her father’s only daughter, and most beloved child. Her brothers – envious and bitter – fought and finally drowned her, whereupon she gained a dolphin tail and took to the Amazon, beautiful and immortal. In this guise and with the sweet music of the splashing waters she lures men to their deaths, and even those who survive never escape their longing for the sparkling waters she lives in.

Harriet Rix studied Biochemistry at the University of Oxford, the History and Philosophy of Science at Cambridge and is now writing a book about how trees shape the world around them, to be published by The Bodley Head in 2025. The aim of this month-long research trip up the Amazon was to look at the tactics used by rare trees that grow on the poor soils of the white-sand forests. After encountering vampire bats, tarantulas and rapids, and being led astray by whiffs of Chanel No. 5 from an Aniba roseadora tree near the Serra Curicuriari she is now hooked, and is hoping to return to climb the Pico da Neblina in 2026.

More on Harriet RixRelated Stories

Adventure In South America

Adventure To The White Continent | Plan South America

An Interview With Our Founder and Director | Harry Hastings For YOLO Journal

@plansouthamerica